Visual exploratory analysis

Introduction

In this lab, we will extend your skills to explore data by visualizing it… and R is great for this! It is actually a highly-demand skill in the job market.

Visualizing data is an important process in at least two stages in quantitative research: First, for you as a researcher to get familiar with the data; and second, to communicate your findings. R includes two important tools to achieve this: First, the wonderful ggplot2 package (included in tidyverse), a powerful tool to explore and plot data. Second, R Markdown which allows you to create integrated quantitative reports. Combining and mastering the two can create very effective results.

Data visualization

Visual data exploration with ggplot2 (Artwork by @alison_horst).

Visualizations are important for any quantitative analysis. These are helpful to identify overall trends, problems, or extreme values in your data at an initial stage. Additionally, visualizations are key to communicate your results at the final stage of the research process. These two stages are known as exploratory and explanatory visualizations, respectively. Base R includes some functionalities to create basic plots. These are often used to generate quick exploratory visualizations. In addition, ggplot2, which is one of the most popular data visualization tools for R, allows you to extend the base R capabilities and create publishable high-quality plots. In this lab we will focus on ggplot2.

Different plot types serve different types of data. In the last lab, we introduced some functions to summarise your data and to generate summaries for specific types of variable. This will help you to decide what the most suitable plot is for your data or variable. The table below presents a minimal guide to choose the type of plot as a function of the type of data you intend to visualize. In addition, it splits the type of plot by the number of variables included in the visualization, one for univariate, or two for bivariate. Bivariate plots are useful to explore the relationship between variables.

| Univariate | Bivariate | |

|---|---|---|

| Categorical | Bar plot / Pie chart | Bar plot |

| Numeric | Histogram / boxplot | Scatter plot |

| Categorical + Numeric | - | Box plot |

Note that it is possible to include more than two variables in one plot. However, as more variables are added, careful considerations are needed on whether they are actually adding more useful information or instead making the graph difficult - or impossible - to interpret.

Setup a new R Markdown file

We will continue working in the same project called NILT in Posit Cloud.

Set up your session as follows:

- Go to your ‘Lab Group ##’ in Posit Cloud (log in if necessary);

- Open your own copy of the ‘NILT’ project from the ‘Lab Group’;

Within your ‘NILT’ project, ensure you are in the top-level project directory. You can tell by checking in the ‘Files’ tab in the bottom-right pane. Near the top of the tab you’ll see “Cloud > project”. If that’s all you see, you are already in the top-level folder. If instead you see “Cloud > project > R” or “Cloud > project > data” then click on the text for “project” to navigate back to the top-level folder.

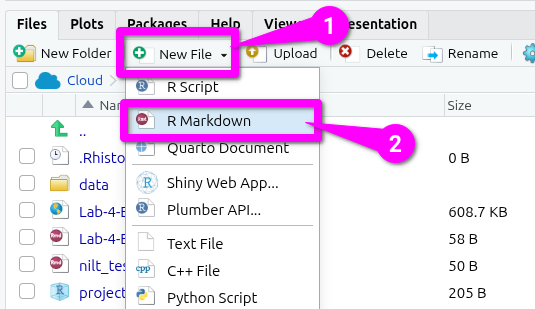

Next, create a new R Markdown document. Within the ‘Files’ tab in bottom-right pane -

- Click ‘New File’ in the tool-bar.

- Select ‘R Markdown’ from the list of options.

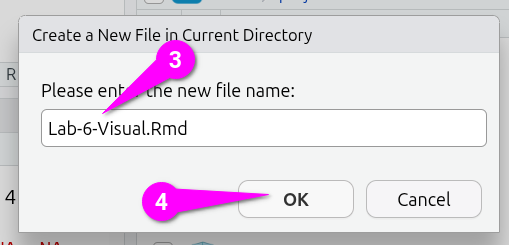

Within the ‘Create a New File in Current Directory’ dialogue that pops up -

- Type

Lab-6-Visual.Rmdas the name. - Click the ‘OK’ button to confirm.

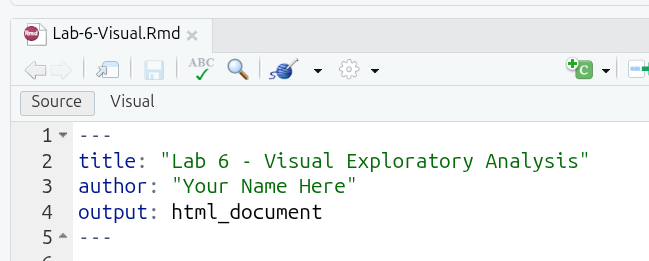

Feel free to then adjust the YAML header, such as adding a more full descriptive title and your name as the author.

Once you have modified the YAML, we next need our setup code chunk with the knitr options. So -

- Create a new code chunk

- Modify the fence options to

```{r setup, include=FALSE} - Then in the main body of code chunk add -

knitr::opts_chunk$set(message = FALSE, warning = FALSE)Then, create another code chunk and name it preamble and again include=FALSE.

Within it, we want to load the tidyverse, read in our NILT file, and setup a subset with the variables we’ll be using.

Run both of the previous chunks individually by clicking on the green arrow located on the top-right of the chunk.

As wee reminder, despite in Lab 4 loading the tidyverse and setting up the nilt and nilt_subset data frame objects, we still need to do this again in each new R Markdown file. The reason for this is whilst they are available in our Global Environment, the top-right pane, each time you ‘knit’ your document it starts with a clean Global Environment. It does this as for reproducibility anyone with a copy of the R Markdown file and data being used should be able to run the code and receive the exact same results.

Now that we have read the data in, we are ready to start creating our own plots using the 2012 NILT survey.

ggplot Syntax

Fortunately, ggplot is part of the Tidyverse set of packages, which places strong emphasis on simplicity, readability, and consistency. As covered in the online lecture for this week, the gg in ggplot stands for “grammar of graphics”. This breaks down graphs into different components that - similar to using grammar to compose words together in a sentence - you compose together to create graphs. This combination of Tidyverse’s overall design philosophy and Wilkinson’s Grammar of Graphics approach, makes ggplot incredibly powerful. We can create complex plots with only a few lines of (relatively) simple code.

At its most basic, ggplot always takes at least three layers, namely data, aesthetics and geometry. It is good practice though to also include text labels - such as a title and labels for x and y axes - to make clear what is being visualised in your plot. In general then, with ggplot we use the general format -

To break this down:

-

data_frameis the data frame object we want to use for our plot, such asnilt_subset. -

ggplot()is the main function to create a new plot and is always the first layer we add. -

aes(), short for “aesthetic mappings”, is used inside theggplot()function to specify which variables from our data frame we want to use. For univariate plots, we can just specify the x or y axis (e.g.data_frame |> ggplot(aes(x = column_name)). It can also take other arguments, which we will cover in sections below. -

+is used between eachfunction()to ‘compose’ them together. It is basically the equivalent of saying “after this function ADD this function”. If you encounter error messages when using ggplot, it is always best to first check whether you are missing any+symbols between functions. -

geom_...(), with “geom” being short for “geometry”, is used to specify the type of plot, such asgeom_boxplot(),geom_histogram(), and so on. We will cover each of these plot types in more detail further into the lab. -

labs()is then used to add our text labels, with main ones to be aware of beingtitle = "",x = "", andy = "".

And that’s it! With often just three lines of code we can construct most plots we will want for our analysis. Importantly, despite all the different plot types we might want to construct, the code we need to write all follow this same basic ‘grammar’. The main bits that will change based on plot type are the precise arguments within the aes() function, which specific geom_...() function we use, and the labels we set using the labs() function. So, pay attention to how those change across the plot types covered below and you’ll have a good sense of all you will need when creating your own plots.

Categorical variables

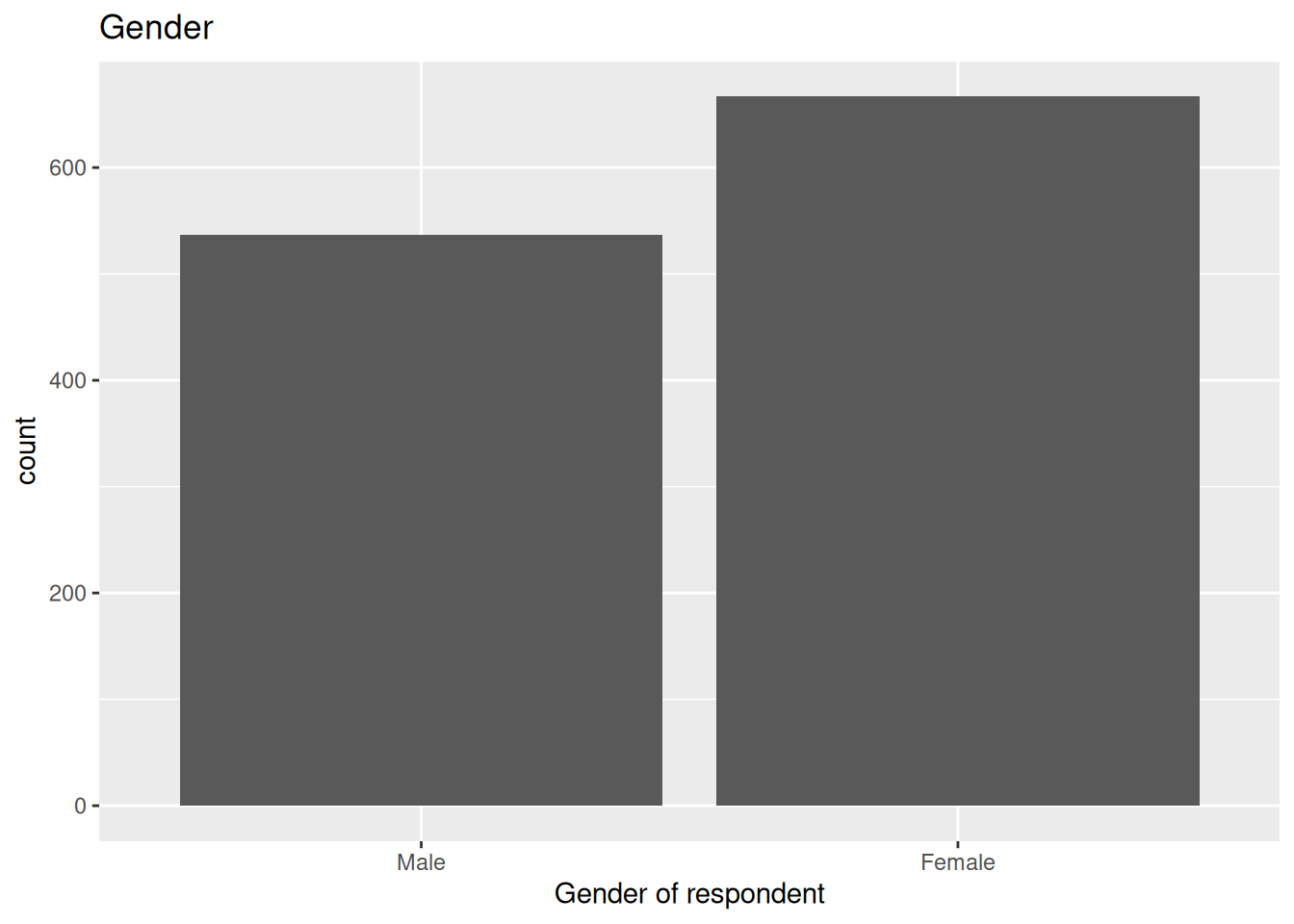

Let’s start using the same variables we summarised in Lab 4. In Lab 4, we started by computing the total number of respondents by gender in a one-way contingency table. We can easily visualize this using a bar plot with ggplot -

(Note: Remember you will need to create a code chunk for adding this code within your R Markdown file.)

Here:

- We pass our data frame object,

nilt_subset, using the pipe operator. Without a pipe, we would need to writeggplot(nilt_subset, aes(.... - Inside the

ggplot()function, we then use theaes(), aesthetics, function. In this case, within it we define the X axisx =of the plot by the categories included in the variablersex. - After

ggplot()we add a+symbol to compose our functions together. - The geometry is specified with the function

geom_bar()without arguments for now. Again we add+after it so R knows to compose the functions we are using together to construct the plot. - Finally, we use the

labs()function to provide labels for the main title -title = "Gender"- and the name of the x axis -x = "Gender of respondent". Note, as this is our last function for constructing the plot, we do not need a+after it.

From the plot above, we can graphically see what we found out previously: there are more female respondents than males in our sample. The advantage is that we can have a sense of the magnitude of the difference by visualising it.

Bivariate categorical vs categorical

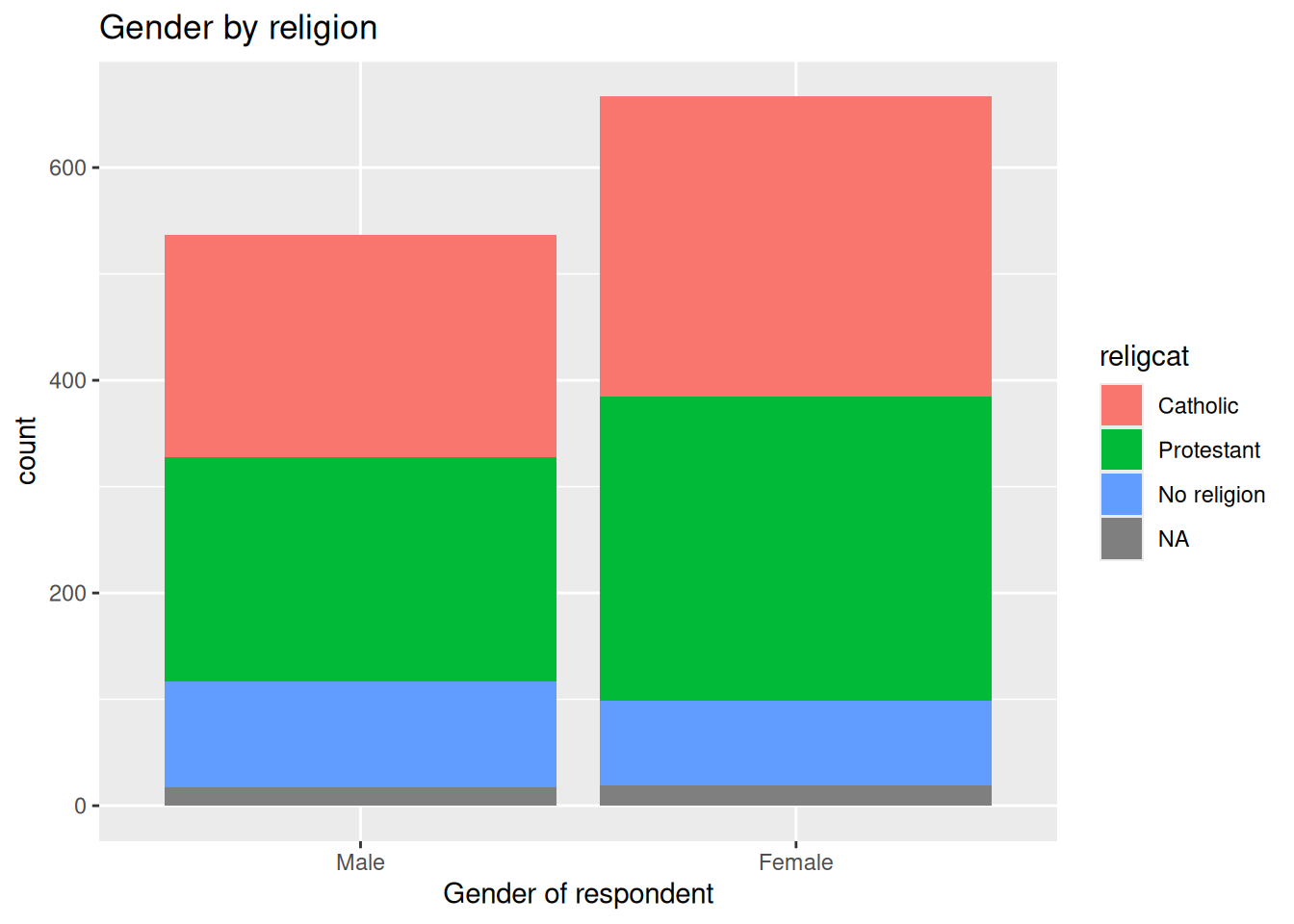

In Lab 4, we computed a Two-Way contingency table, which included the count of two categorical variables. This summary can be visualized using a stacked bar plot. This is quite similar to the above, with the addition that the area of the vertical plot is coloured by the size of each group.

If we wanted to know how gender is split by religion, we can add the fill argument with a second variable in aesthetics, as shown below.

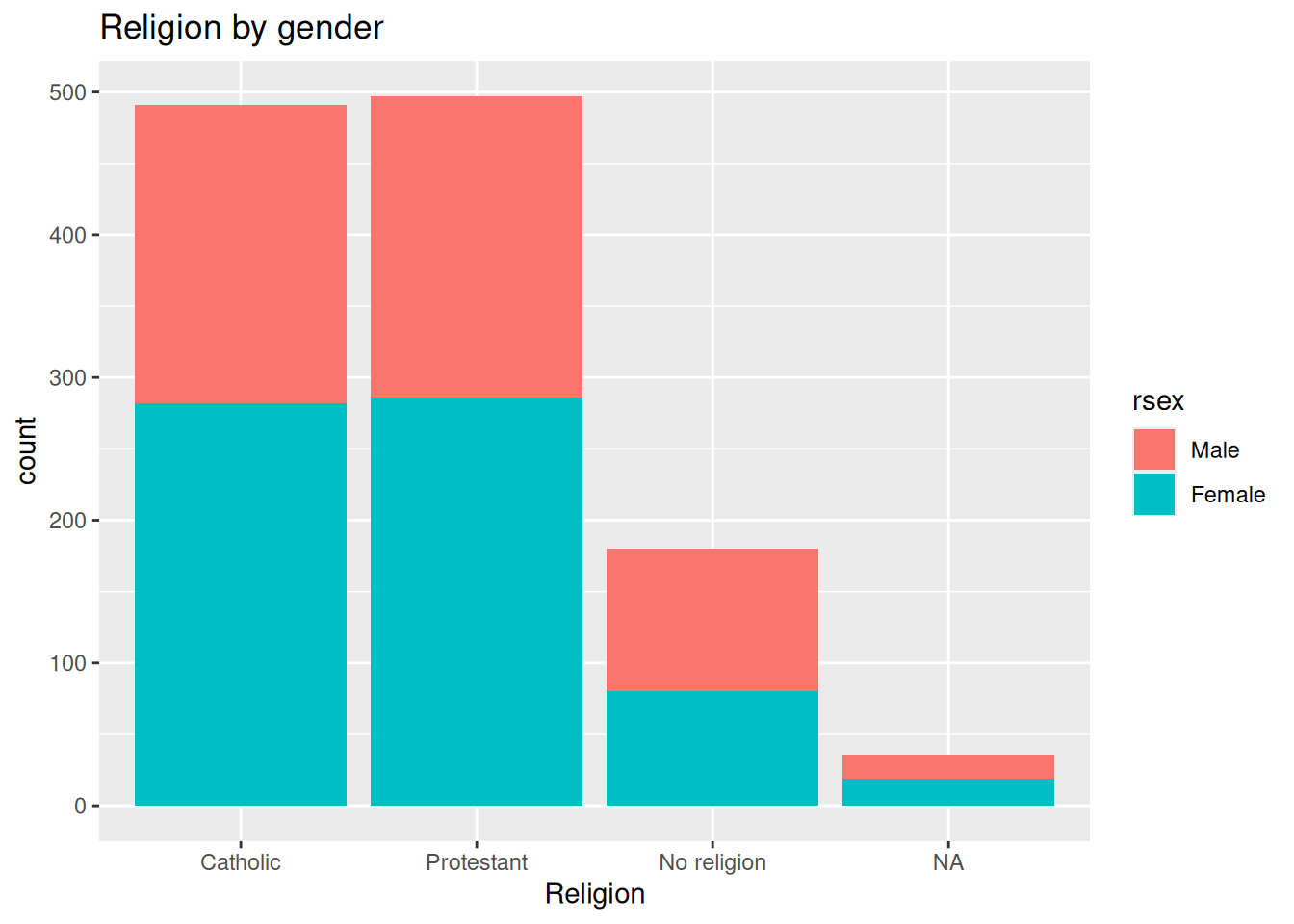

This plot is not very informative, since the total size of female and male respondents is different. The type of visualization will also depend on your specific research question or the topic you are interested in. For example, if I think it is worthwhile visualizing the religion by respondents’ sex. A plot can show us the magnitudes and composition by respondents’ sex for each religion. To do this, we need to change the aesthetics, specifying the religion by category variable religcat on the x axis and fill with gender rsex.

As we can see, Catholic and Protestant religion are similarly popular among the respondents. Also, we can see that these are composed by similar proportions of males and females. One interesting thing is that there are more male respondents with no religion than female participants. Again, we found this out with the descriptive statistics computed in Lab 4. However, we have the advantage that we can graphically represent and inspect the magnitude of these differences.

Numeric variables

Univariate numeric

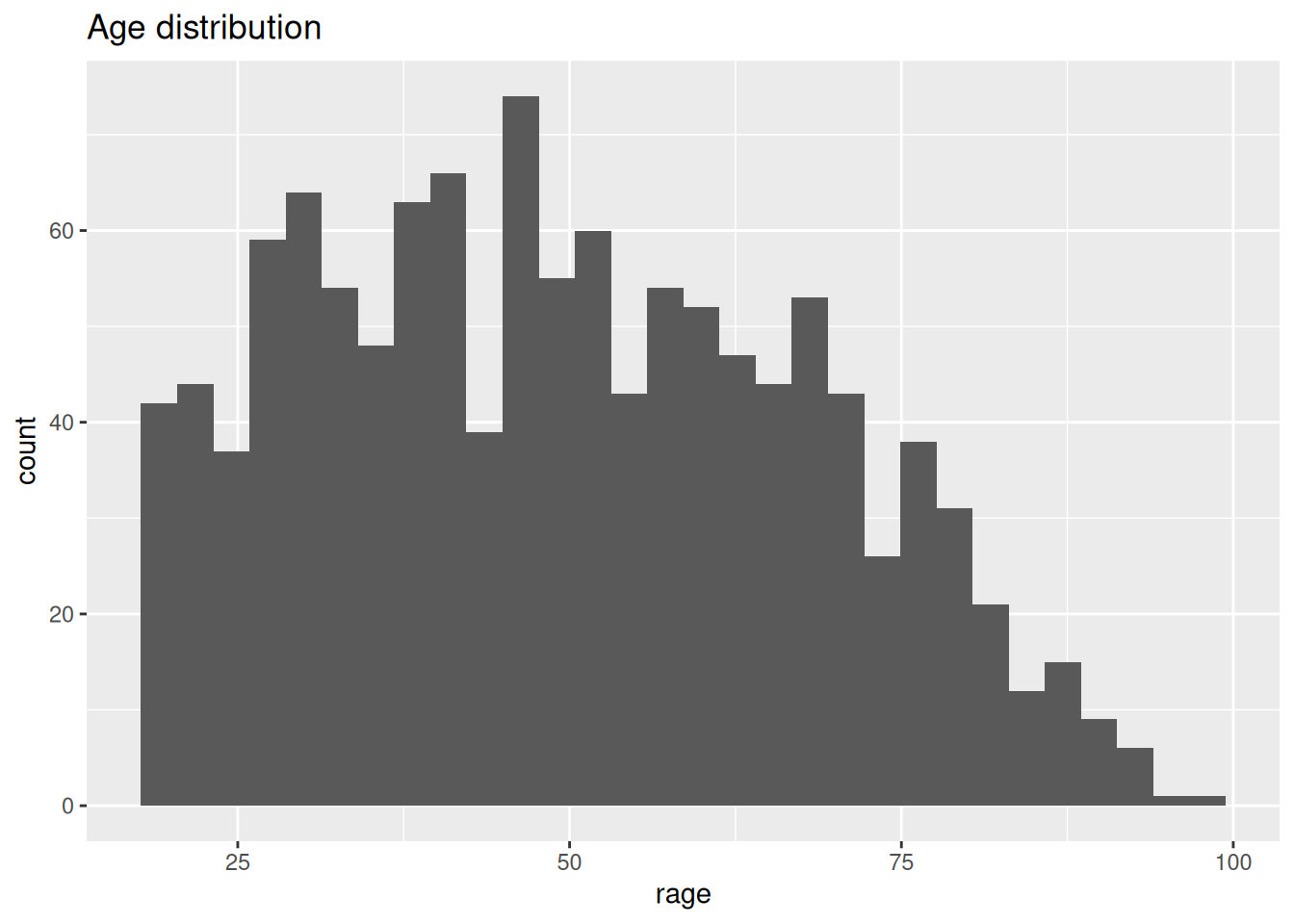

In Lab 4, we talked about some measures of centrality and spread for numeric variables. The histogram plot is similar to the bar plot; the difference is that it splits the numeric range into fixed “bins” and computes the frequency/count for each bin instead of counting the number of respondents for each numeric value. The syntax is practically the same as the simple bar plot. This time, we will set the x aesthetic with the numeric variable age rage. Also, the geometry is defined as a histogram using the geom_histogram() function.

nilt_subset |> ggplot(aes(x = rage)) +

geom_histogram() +

labs(title = "Age distribution")

From the histogram, we have age (in bins) on the X axis, and the frequency/count on the y axis. This plot is useful to visualize how respondent’s age is distributed in our sample. For instance, we can quickly see the minimum and maximum value, or the most popular age, or a general trend indicating the largest age group.

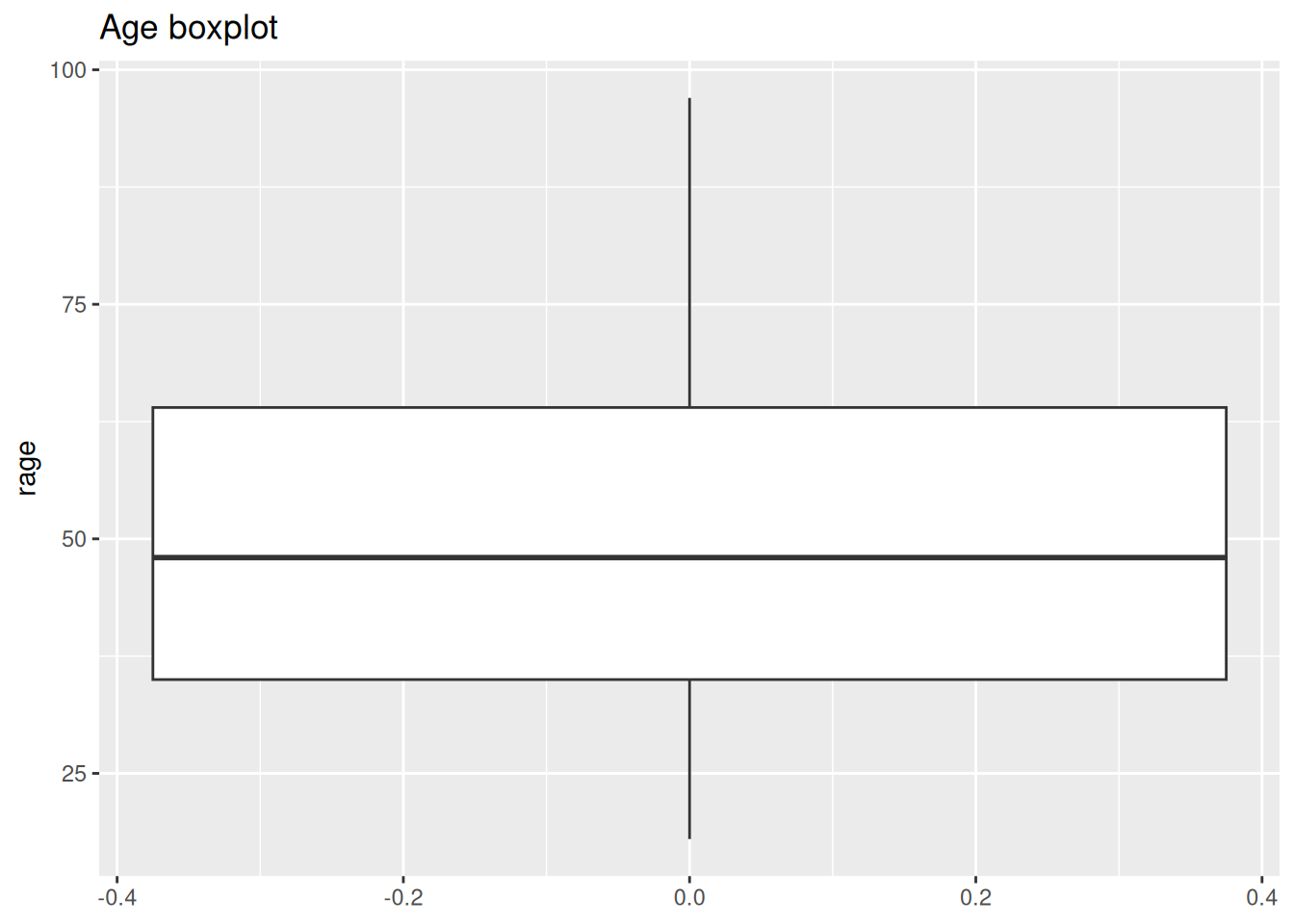

A second option to visualize numeric variables is the box plot. Essentially this draws the quartiles of a numeric vector. For this plot, rage is defined in the y axis. This is just a personal preference. The geometry is set by the geom_boxplot() function.

nilt_subset |> ggplot(aes(y = rage)) +

geom_boxplot() +

labs(title = "Age boxplot")

What we see from this plot is the first, second and third quartile. The second quartile (or median) is represented by the black line in the middle of the box. As you can see this is close to 50 years old, as we computed using the quantile() function. The lower edge of the box represents the 2nd quartile, which is somewhere around 35 years old. Similarly the 3rd quartile is represented by the upper edge of the box. We can confirm this by computing the quantiles for this variable.

quantile(nilt_subset$rage, na.rm = TRUE) 0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

18 35 48 64 97 Bivariate numeric

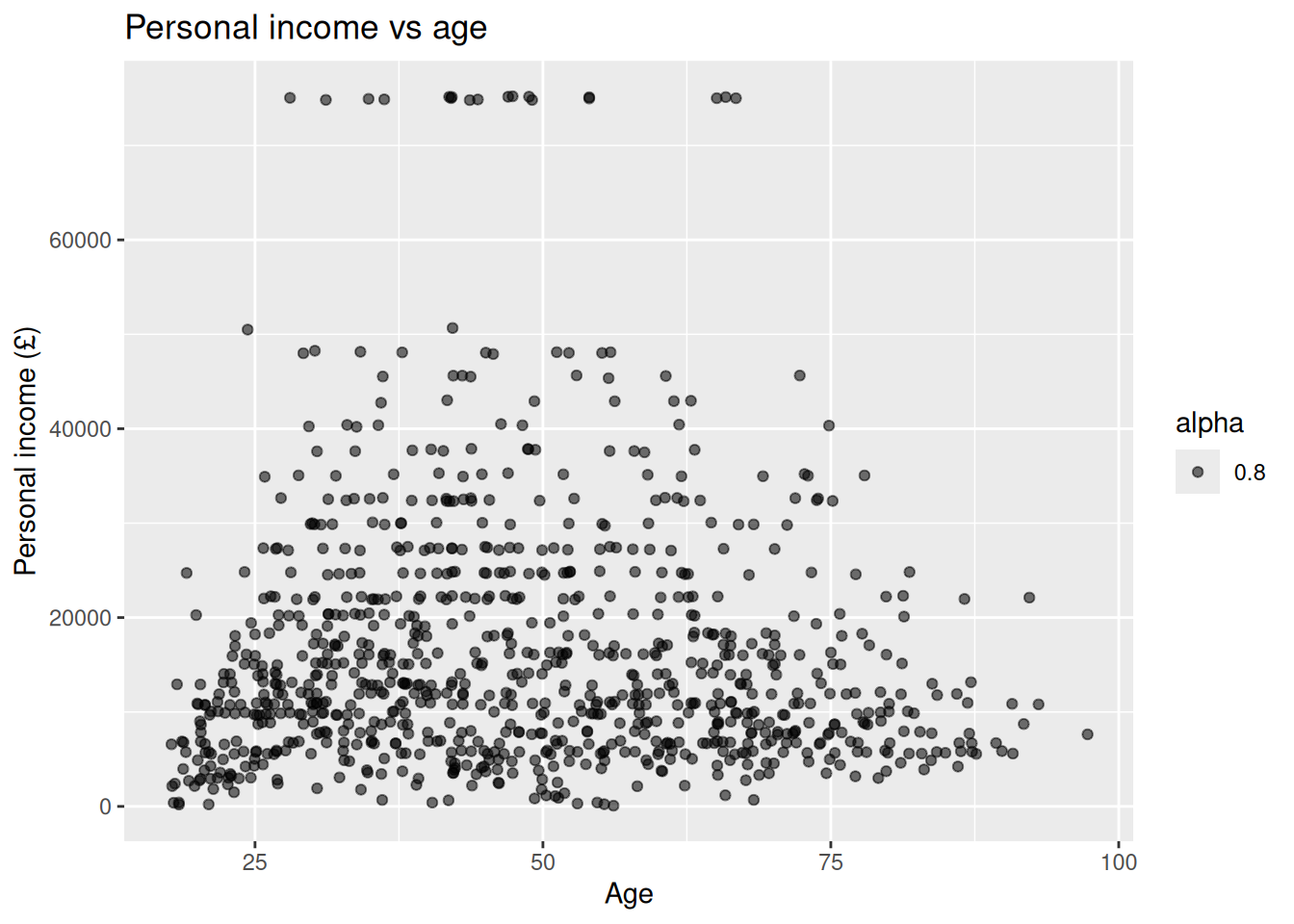

A useful plot to explore the relationship between two numeric variables is the scatter plot. This plot locates a dot for each observation according to their respective numeric values. In the example below, we use age rage on the X axis (horizontal), and personal income persinc2 on the Y axis (vertical). This type of plot is useful to explore a relationship between variables.

To generate a scatter plot, we need to define x and y in aesthetics aes(). The geometry is a point, that we can specify using the geom_point() function. Note that we are specifying some further optional arguments within geom_point(). First, alpha regulates the opacity of the dots. This goes from 0.0 (completely translucent) to 1.0 (completely solid fill). Second, in we defined position as jitter. This arguments slightly moves the point away from their exact location. These two arguments are desired in this plot because the personal income bands overlap - meaning most points will be drawn directly ontop of each other. Adding some transparency and noise to their position with jitter (i.e. shifts dots slightly apart), can make it easier to visualize possible patterns.

nilt_subset |> ggplot(aes(x = rage, y = persinc2)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.7, position = "jitter") +

labs(title = "Personal income vs age", x = "Age", y = "Personal income (£)")

There is not a clear pattern in our previous plot. However, it is interesting to note that most of the people younger than 25 years old earn less than £20K a year. Similarly, most of the people older than 75 earn less than £20K. And only very few earn over £60k a year (looking at the top of the plot).

Mixed data

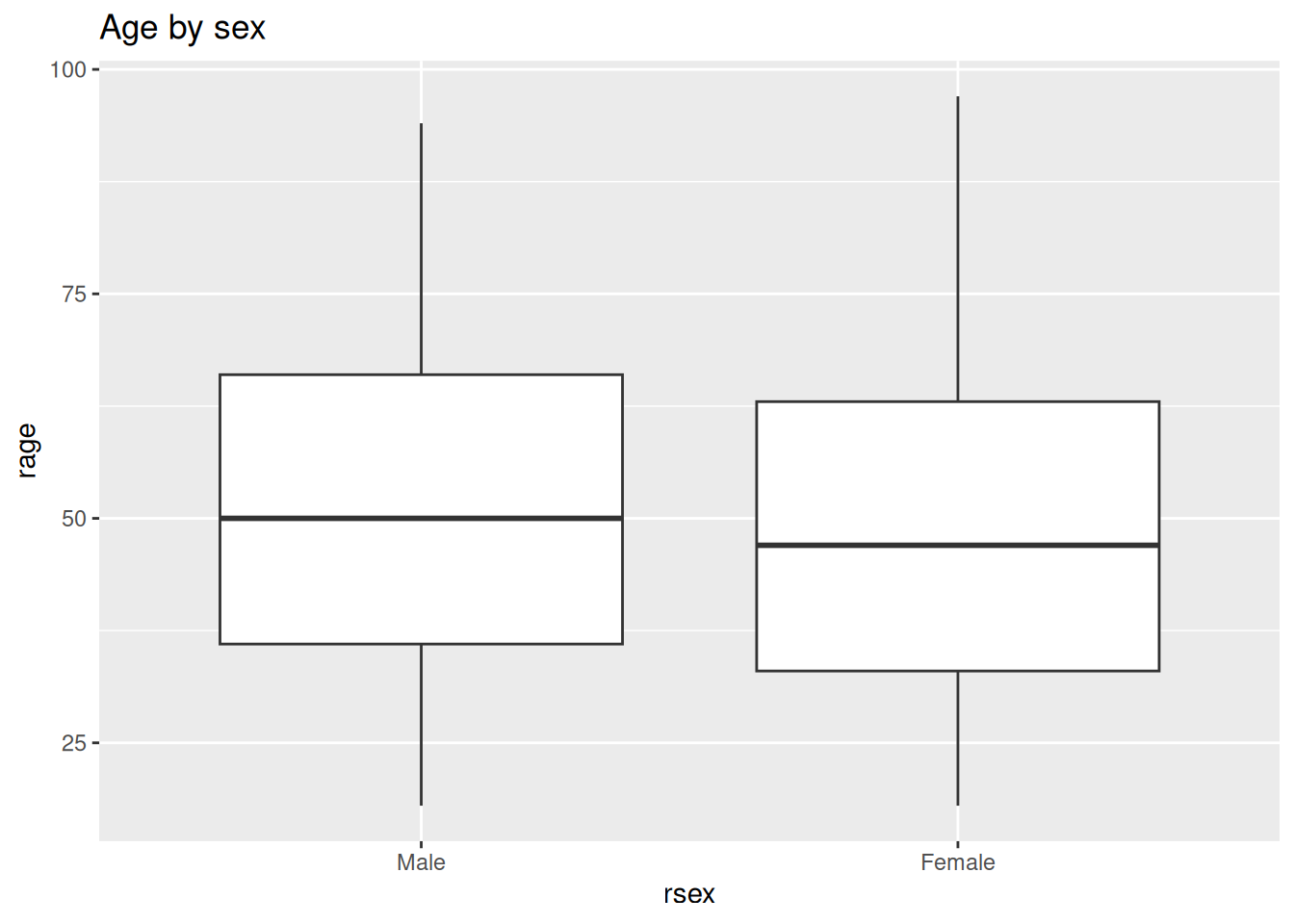

Very often we want to summarise central or spread measure by categories or groups. For example, let’s go back to the example of age and respondents’ sex. We can visualize these two variables (which include one numeric and one categorical) using a box plot. To create this, we need to specify the x and y value in aes() and include the geom_boxplot() geometry.

nilt_subset |> ggplot(aes(y = rage, x = rsex)) +

geom_boxplot() +

labs(title = "Age by sex")

From this, we can visualize that female participants are slightly younger than their male counterparts in the sample.

R Cheatsheets

There are a number of features that you can customize in your plots, including the background, text size, colours, adding more variables. But you don’t have to memorise or remember all this, one thing that is very commonly used by R data scientists are R cheat sheets! They are extremely handy when you try to create a visualisation from scratch, check out the Data Visualization with ggplot2 Cheat Sheet. An extra tip is that you can change the overall look of the plot by adding pre-defined themes. You can read more about it here. Another interesting site is the The R Graph Gallery, which includes a comprehensive showcase of plot types and their respective code.

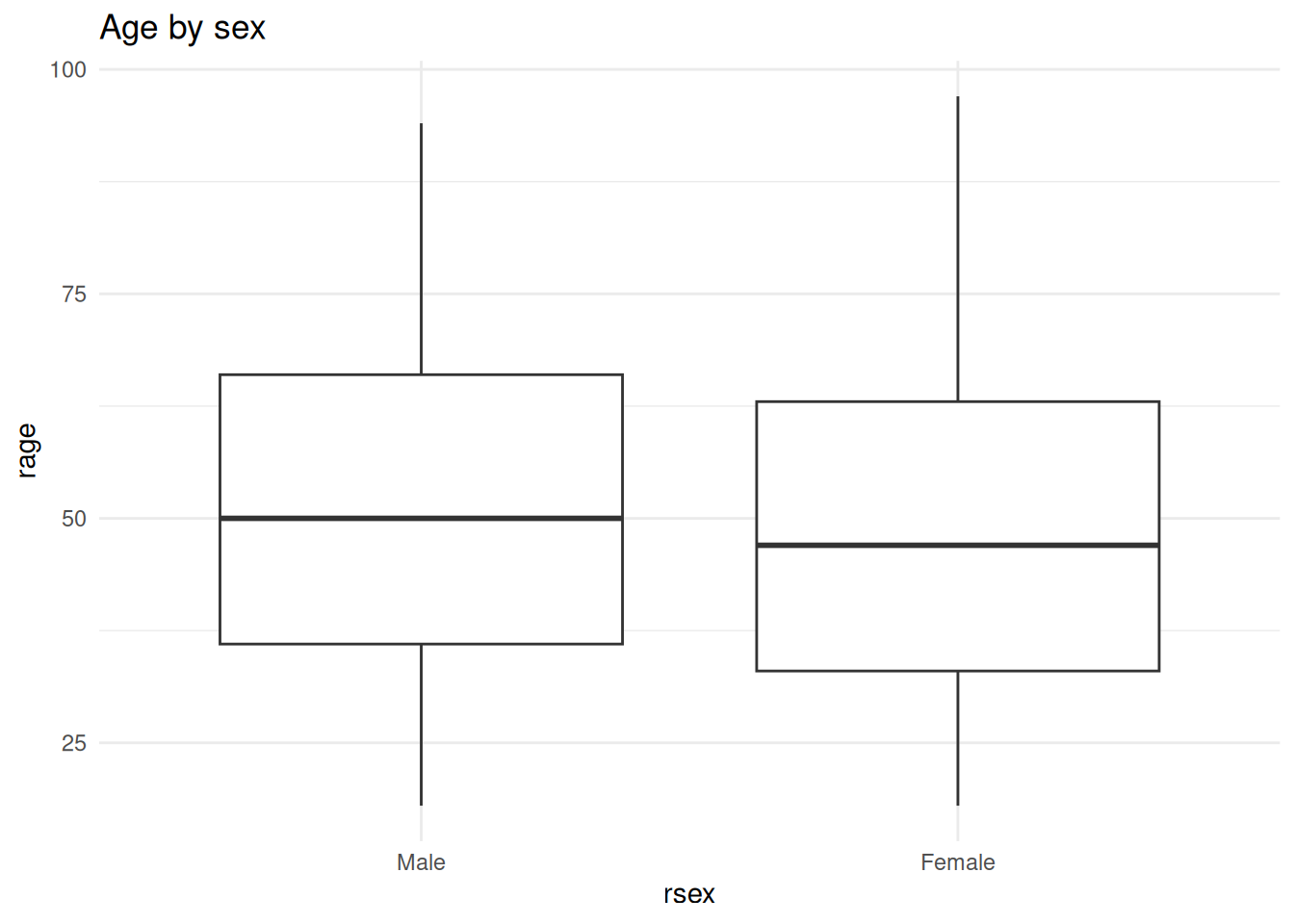

As a quick example of how simply themeing is, let’s take the last graph and apply a minimal theme. All we need to do is add + after labs() followed by theme_minimal().

nilt_subset |> ggplot(aes(y = rage, x = rsex)) +

geom_boxplot() +

labs(title = "Age by sex") +

theme_minimal()

Rather than adding + theme_...() to each plot individually, you can also set a global theme using theme_set(). As this is setting a theme to use for all plots, by convention the code for this would be added to your “preamble” code chunk at the top of your R Markdown document.

# Set ggplot theme

theme_set(theme_minimal())After adding (and running) the code, any code you run to create a plot will use the minimal theme.

Important. If you are interested in applying a theme to your plots please look at the linked resources above. Themeing plots is easy with ggplot, with a number of built-in themes available with a single function. Despite that, if you prompt genAI how to write code for a plot, it will often add a theme - even when one was not requested, add arbitrary and needlessly complex customisation, and inconsistently apply these themes/customisations across plots.

As a general rule of thumb, if genAI responses have code we did not cover in the labs, 99% of the time you can be confident it is spouting out absolute nonsense. As seen above, the built-in ggplot themes can be applied with a single line of code, and more complex customisation - that you will rarely, if ever, need - can be set once globally or used only when absolutely needed for a specific plot. GenAI will mislead you into thinking that creating plots with R requires 20+ lines of code rather than 3-4. It has similar issue with tables, sometimes giving 40+ lines of code to create a table that could instead be created with a single line of code.

Activity

Using the nilt_subset object, complete the tasks below in your R Markdown file. Insert a new code chunk for each of these activities and include brief comments as regular text (i.e. outside the code chunk) to introduce or describe the plots. Feel free to copy and adapt the code to create the plots in the examples above. As covered in the lectures, you do not need to memorise the exact code. The important thing is that you understand what the code does and how to modify it for what you are trying to achieve.

- Create a first-level header to start a section called “Categorical analysis”;

- Create simple bar plot using the

geom_bar()geometry to visualize the view on unionist/nationalist/neither affiliation reported by the respondents using the variableuninatid; - Based on the plot above, create a ‘stacked bar plot’ to visualize this affiliation by religion, using the

uninatidandreligcatvariables; - Create a new first-level header to start a section called “Numeric analysis”;

- Create a scatter plot about the relationship between personal income

persinc2on the Y axis and number of hours worked a weekrhourswkon the X axis; - Finally, create a box plot to visualize personal income

persinc2on the Y axis and self-reported level of happinessruhappyon the x axis … Interesting result, Isn’t it? Talk to your lab group-mates and tutors about your results. - Add your own (brief) comments to each of the plots as text in your R Markdown file;

- Knit the .Rmd document as HTML. The knitted file will be saved automatically in your project.